Question: "Wasn't the Bible we have today edited and redacted by the Council of Nicaea, with writings arbitrarily hand picked to support the emperor's claims to power, and then later further edited and altered by medieval popes?"

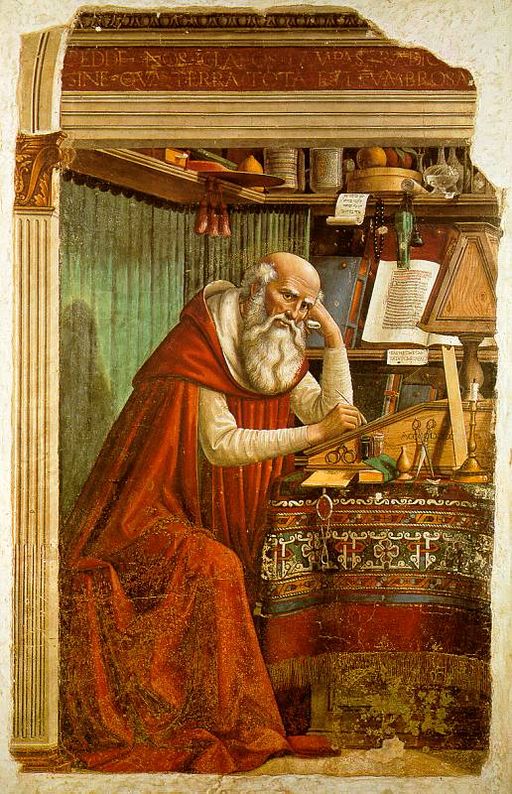

(Image: "Saint Jerome in his study", by Domenico Ghirlandaio, Public Domain, obtained from Wikimedia Commons)

Short answer: "no".

I have elsewhere addressed the issue of New Testament "canon", which was posed in an essentially identical question. However, I will take the opportunity now to address briefly the point about medieval popes. The western Christian church, originating from the Latin speaking lands of the Roman Empire, relied upon a Latin translation of the Bible, known as the versio vulgata, or the "version commonly used" (a word of similar derivation is "vulgar" which originally meant "common"). The Vulgate was largely the work of Saint Jerome, who translated various earlier texts. This was never further altered or edited by popes. It remained the only Bible of the western church for centuries, until other translations were available.

Of course, after the fall of Rome, Europe became peopled by Germanic invaders for whom Latin was not their first language. The Goths, Franks, Huns, Norsemen, Brits, Angles, and Jutes all spoke their own languages. Latin remained the official language of the church and the people relied upon priests and the church to interpret for them what was in the Vulgate. Although in use for a millennia, it was not until around 1590 at the Council of Trent that the Vulgate was declared the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church.

Something remarkable did happen, beginning in the 14th century, with the flowering of study in ancient languages that occurred during the Renaissance. Greek and Hebrew manuscripts that had been previously neglected were once again examined, and the Bible was studied in its original languages. This in turn paved the way for the Protestant Reformation's differing understanding of justification, as in Romans 1:17, where it says "the just shall live by faith."

In 1517, Martin Luther was a learned monk and professor at the University of Wittenberg, who was lecturing on Paul's Letter to the Romans. He turned to the original Greek manuscripts as well as to the Latin version of the Bible. He wondered what was meant by the word "just" (justificare in the Vulgate), and was hit with an epiphany: the Greek word dikaios was the actual word used by Paul, and connoted a sense of being declared or regarded as just (such as at the end of a trial when a person is declared "not guilty" or "not guilty by reason of insanity"--in this case "not guilty by reason of Christ's blood"). The Latin version has the meaning "to become or be made just". For Luther and all who follow in his steps, the real meaning of the gospel is that we can't earn favor with God, we must rely wholly on the grace of God, by which we are declared to be just.

A full discussion of the doctrines of justification, or the differences between Roman Catholicism and other branches of Christianity is beyond the scope of this little essay. To redirect back to the question at hand, the Latin version of the Bible is very ancient, and was passed down for millennia untouched by kings, unaltered by popes, and un-redacted by councils.